Liss C. Werner is Professor of ‘Bio-Inspired Architecture and Sensoric, CyPhyLab at the Institute of Architecture, TU Berlin. She is a registered architect and the founding director of Tactile Architecture. She practiced in the UK, Russia, and Germany. Liss research focuses on cybernetics in the discourse of computational architecture as a discipline of socio-ecological systems between technology, human, and nature; it combines material, geometry, biology, data and the sensory. Liss C. Werner takes us through her professional level and shares her experience as a Professor.

Could you tell us a little about yourself and your professional journey?

I grew up in a small town in Germany before starting my education as to be an architect. In Hamburg, I trained to be a draftsman for two years. I then moved to the UK for my studies and spent one year, 1998, as an exchange student in Australia at RMIT. My academic career began at the end of my studies as a studio master at the University of Nottingham. My international education and joy of travel took me to Carnegie Mellon University as a guest professor and to Malaysia, Finland, Austria, Portugal, Ukraine, the US, and the Bauhaus town Dessau, to name a few places. Practice started right after my high-school graduation, and I was lucky to work in the UK, Russia, and Germany.

Why have you chosen to be an Architect?

This is a great question. I think the profession has chosen me, not the other way around. My great-granddad was the founder of a sawmill, and in the 1950s, the company produced pre-fabricated building components made of timber. As a kid, I was fascinated by the way how a tree becomes something else. Also, having chosen to be an architect derives from my dad’s pleasure in architecture, my mum’s fascination with complexity and systems, and my passion for building and constructing things. Later, I realized that small urban and architectural interventions could change a seemingly irrelevant space to a place of social interaction. Finally, the ability and gift to create beautiful things is rewarding and indeed wonderful to share.

When have you started to focus on “Cybernetic” and “sensorial” Architecture?

In 2003 at the Bartlett School of Architecture, I came across the cybernetician Gordon Pask. He triggered my curiosity about how systems, sensors, and interaction are related, an organizational construct observed in architecture and urban design. Luckily, I then received mentorship on Design Cybernetics from his students Ranulph Glanville and Paul Pangaro (CMU). My focus on cybernetic and sensorial architecture gets stipulated each time I tackle a new architectural problem.

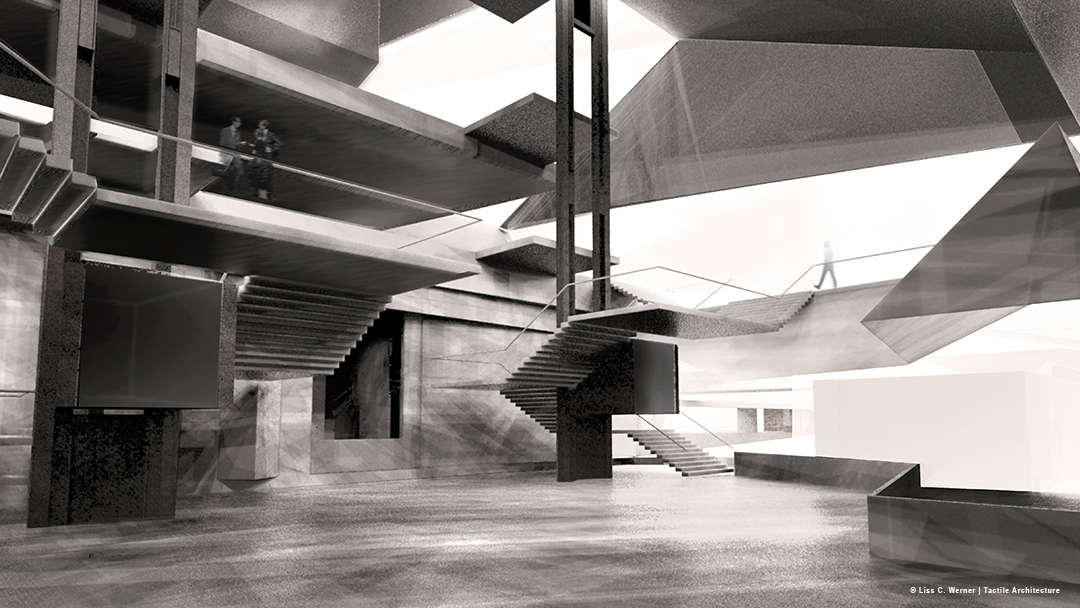

Kipisland interior

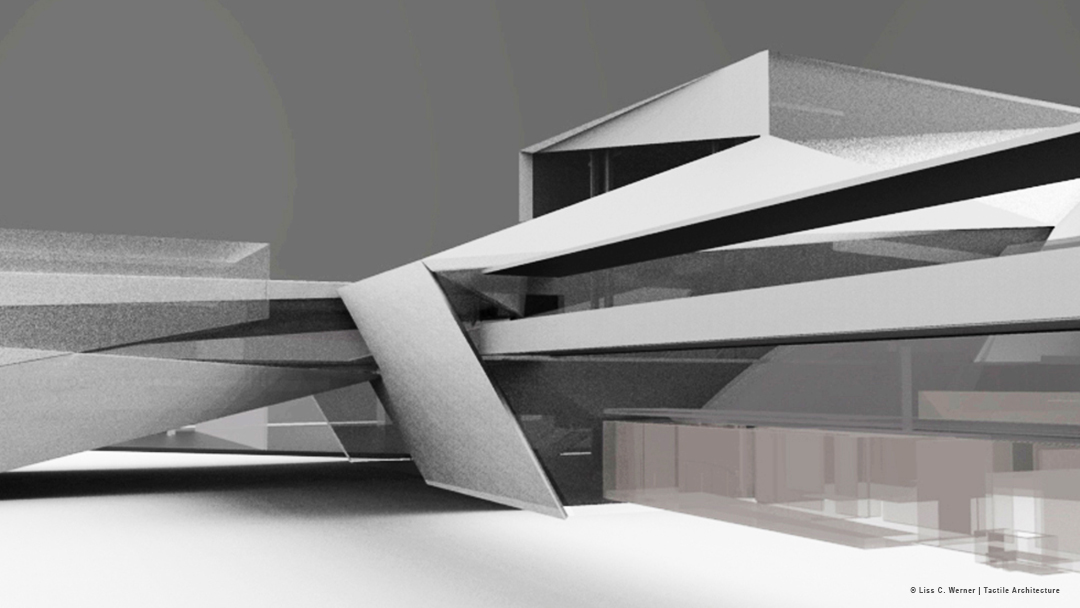

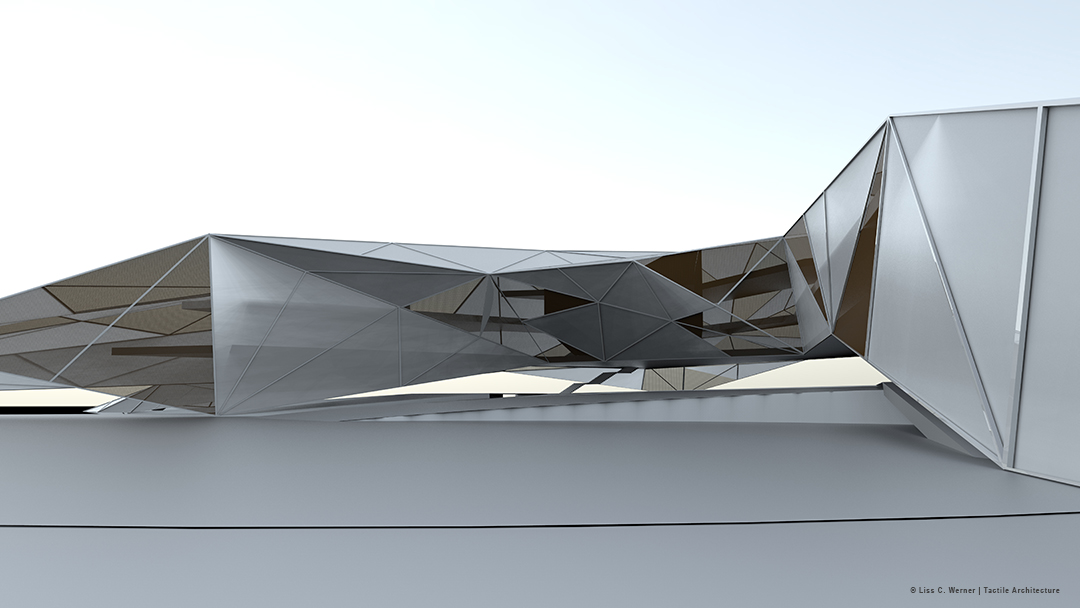

Kipisland office bridge

You founded the “Tactile Architecture” Studio in Berlin, can you share with us some of the projects you and your team have been working on?

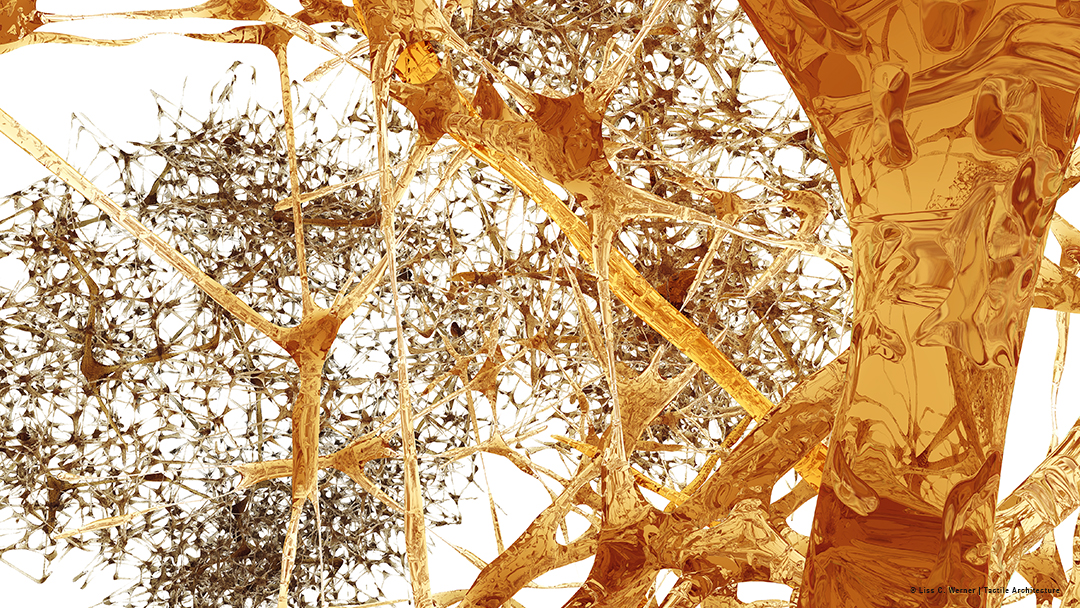

A great project we worked on was a competition for the 15000m2 large Kipsala Island Auditorium in Riga, Latvia. The project entailed the transformation and extension to the existing international exhibition center and grounds in collaboration with the Riga Expo Centre next to the Zunds canal, famous for kayaking. We enveloped the existing building with flying stairs, cantilevering galleries, and elevated boxes. The design was driven by the concept of the bridge and the view. Another project was a scripted animated simulation of an in-silico biologically grown underwater habitat and infrastructure, connecting points on an island in the North Sea of Germany with selected points on the East Frisian mainland. The project was derived from our observations of the biological organism physarum polycephalum. We showcased the work as a movie at the Design Computing Exhibition curated by the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Prague.

As a University Professor, do you mind disclosing some of your research topics?

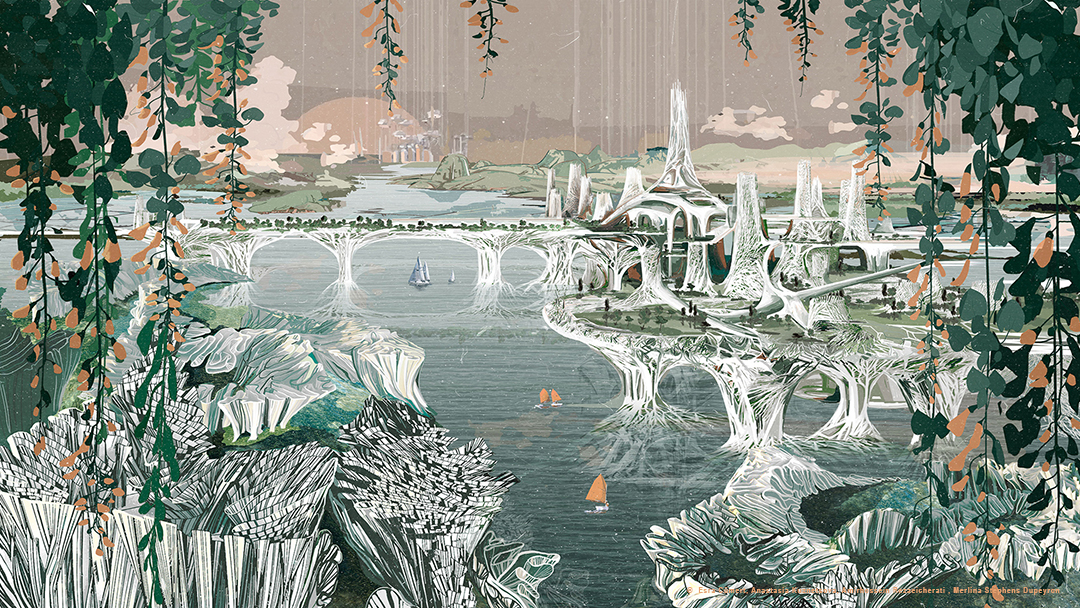

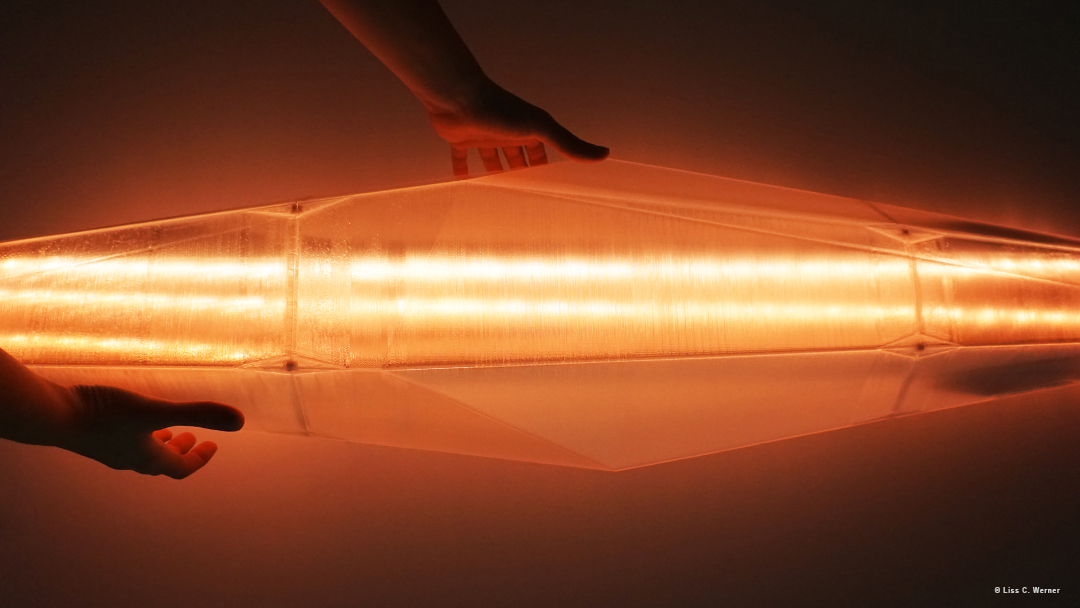

Our research topics are pretty broad in principle. Principles of biological organisms are just as important as intelligent lighting for crowd guidance or data analysis in workplaces to increase visual or acoustic comfort. Our design research is mostly data-driven and fosters feedback and interaction between artificial senses, such as proximity, sound or light sensors, and users. We utilize open data, such as climate data, to shape the geometry of e.g., façade panels. Material and space act as an interface to somehow humanify technology. Thus, we design and construct our intelligent objects ourselves using 3D printing and knowledge in sensor/hardware technology. On an urban level, our key topic is the future morphological and material transformation of our cities, our urban human habitats.

SOCO Phy

TUB Mousserons

TUB Super Organism

What is the most rewarding part for you about teaching at University?

Seeing my students observing, and indeed struggling, with curiosity and passion – and learning. I follow some of them, and some keep following me over the years, sometimes asking for advice. It makes me very happy to see them thrive.

Last, what are the advice and professional tips you give to your students?

Don’t stop following your dream. Draw by hand. Study the masters. Enjoy every mistake you make. Work with physical material to embody your profession. Be aware that the profession and the architect’s role are changing rapidly, so make sure you embrace the magic you, as architects, can create. Read ‘The Fountainhead’, 1943, ‘In Praise of Shadows’, 1933, and ‘Invisible Cities’, 1972. And remember, nature is our best teacher.

Liberty Island exterior

HK 02 human

https://cyphylab.chora.tu-berlin.de/