We are thrilled to announce the launch of the BLT Built Design Awards Winners 2025 Catalogue, now available for free download on our website or for purchase on Amazon worldwide.

This exclusive publication showcases the exceptional projects and innovations honored in this year’s awards, spanning Architectural Design, Interior Design, Landscape Architecture, and Construction Product Design. Inside, you’ll find inspiring interviews and groundbreaking designs that push the boundaries of creativity and functionality.

The BLT Built Design Awards celebrate the expertise of professionals shaping the built environment—visionary architects, interior designers, landscape architects, and construction innovators—who tackle today’s urbanization challenges and pave the way for the future.

As part of Bangkok Design Week, two curated talks organised by 3C Awards Group will take place on February 1st at the Thailand Creative & Design Center (TCDC). Hosted at the Resource Center Library on the 4th floor of the Grand Postal Building, the sessions bring together international designers, architects, and brand leaders to explore how design shapes cities, products, and everyday life.

Bangkok Design Week has long been a fixture on the city’s cultural calendar, playing a central role in strengthening Thailand’s creative industries and positioning Bangkok within the UNESCO Creative City Network as a City of Design. Organised by the Creative Economy Agency (CEA) in collaboration with more than 60 state agencies, public organisations, academic institutions, and international partners, the festival brings together over 2,000 designers and creative businesses and attracts an estimated 400,000 visitors from Thailand and abroad. Across five editions, Bangkok Design Week has welcomed more than 1.75 million visitors and generated an economic value of approximately 1.368 billion baht, underlining its cultural and economic impact.

Within this context, 3C brings an international curatorial lens to Bangkok Design Week, presenting two talks that reflect how contemporary design operates across radically different scales, from national public infrastructure to globally competitive consumer brands.

13:30–14:00

The first talk explores how a new sports brand can be built through close collaboration between designer and founder, aligning product innovation, brand identity, and physical retail experience.

The session is led by Sébastien Maleville, Co-Founder and Creative Director of Essential Studio. Born in France and trained in industrial design in Paris, Maleville has built an international career spanning Europe, China, and Southeast Asia. From 2014 to 2024, he served as Creative Director and Branch Manager at Jacob Jensen Design, while also lecturing in industrial design at King Mongkut University of Technology Thonburi in Bangkok. In 2024, he co-founded Essential Studio, a Bangkok-based design and strategy studio focused on sustainability-driven innovation, responsible products, and long-term brand development.

Joining him is Watee Wichiennit, Founder and Managing Director of VING Thailand. A recreational runner, Watee launched VING in 2019 after struggling with discomfort from traditional running shoes. His pursuit of function-led performance led to the creation of VING NIRUN, the world’s first flip-flop equipped with carbon-plate technology and advanced foam, redefining expectations around running sandals and challenging the dominance of conventional running footwear.

Together, the speakers will unpack how VING’s core values, rooted in performance, natural movement, and innovation, were translated into product design, visual language, and spatial storytelling. The talk examines how Essential Studio and VING collaborated to shape the brand from early positioning through to the design of its flagship retail space at Bangkok’s National Stadium, creating a store that functions both as a commercial platform and a community hub.

Sébastien Maleville is a Jury Member of the SIT Furniture Design Award, while VING Thailand has received international recognition at the FIT Sport Design Awards 2025 and the Global Footwear Awards 2025, highlighting the impact of strong design partnerships and product-driven brand building.

14:00–14:30

The second session shifts focus from consumer brands to civic infrastructure, presenting a landmark case study in regenerative landscape design for government environments.

The talk is presented by Siriwat Jirawattananon, Landscape Architect and Design Director at Landprocess, and Sajjapongs Lekuthai, Landscape Architect and Managing Director of the firm.

Siriwat Jirawattananon is recognised as a new-generation practitioner integrating computational analysis and evidence-based design into landscape and urban projects. His work focuses on transforming complex urban data, including flood risk, urban heat island effects, and environmental pollution, into practical, nature-based solutions. He has led major public and institutional projects such as Puey Ungphakorn Centenary Park, Chong Nonsi Canal Park, and the 100th Anniversary renovation of Lumphini Park.

Sajjapongs Lekuthai specialises in the strategic management of large-scale landscape and urban resilience projects, combining design expertise with business and feasibility insight. His work centres on translating climate adaptation strategies into buildable, high-impact projects across public infrastructure, institutional green innovation, and mixed-use developments.

Together, they present the transformation of the Thailand Government Complex, one of Southeast Asia’s largest administrative hubs. The project reclaimed over 18.5 acres of impermeable surface, replacing car-dominated areas with green plazas, shaded walkways, and a central civic lawn. Regenerative strategies include rainwater catchment systems and bioswales for stormwater management, extensive tree planting to reduce urban heat, and solar panels that now supply more than half of the complex’s energy needs.

The speakers will share how these design decisions were developed, the challenges encountered during implementation, and the lessons learned from working within a government framework. In 2025, the project received Landscape Architecture of the Year at the BLT Built Design Awards, recognising its leadership in people-centred, climate-resilient public space design.

Through its presence at Bangkok Design Week 2026, 3C Awards supports this year’s theme, “DESIGN S/O/S: Secure Domestic / Outreach Opportunities / Sustainable Future”, a call for the design industry to respond actively to a world that feels fragile, complex, and constantly changing.

As uncertainty, anxiety, and pressure shape everyday life, design risks being reduced to something decorative or secondary and this theme pushes back against that idea, introducing design as a tool for adaptation, problem-solving, and positive change. It invites designers to think optimistically, collaborate across disciplines, challenge conventions, and design with purpose beyond aesthetics. The two talks curated by 3C Awards reflect this mindset in practice, moving from regenerative public landscapes that rethink how cities serve people to performance-driven brands that challenge established product categories. This programme is made possible through 3C’s partnership with the European Product Design Awards (EPDA), who are managing the local talk sessions on behalf of 3C.

In this conversation, we speak with Kotchakorn Voraakhom, founder of Landprocess and recipient of the Landscape Architecture of the Year award at the BLT Built Design Awards, about the transformation of the Thailand Government Complex in Bangkok. One of the country’s most important administrative hubs, the complex has long reflected the priorities of institutional power, scale, and control. Today, it is being reimagined as something radically different: a civic landscape designed around people, access, and care.

Spanning Zones A, B, and C, the project retrofits a car-dominated government campus into a network of walkable green spaces, shaded promenades, and public plazas, reclaiming vast hard surfaces and integrating blue–green infrastructure directly into everyday experience. Rather than treating sustainability as an add-on, the redesign integrates mobility, water management, cooling, and social life into a single, visible system that supports climate resilience while reshaping how citizens encounter their government.

In the following interview, Kotchakorn Voraakhom reflects on growing up in Bangkok with limited access to public green space, the long and complex process of transforming a formal government campus, and what it means to design a people-first model of governance through landscape architecture. The conversation reveals how trust, collaboration, and long-term commitment can turn public infrastructure into a living civic space, and why care may be the most powerful design tool of all.

Can you tell us about your background? How did you first become interested in landscape architecture, and how did that path lead you to work on the Thailand Government Complex?

My path to this project feels less like a coincidence and more like a calling, though it’s hard to put into words. Growing up in Bangkok—a city at great environmental risk and with among the least public green space per capita in the world—I felt the absence of public space deeply. I knew I wanted to help create places where people could breathe, connect, and truly enjoy their city, long before I knew it was called landscape architecture.

This conviction led to projects that became stepping stones. After completing the Chulalongkorn Centenary Park—Bangkok’s first major public park in 30 years—my team and I learned that each accomplishment doesn’t make the work easier; it prepares you for greater challenges. It opens the door to larger, more complex missions.

That is how the path led here: through a commitment to public life and a proven readiness to take on transformative civic projects. When the opportunity arose to reimagine the Thailand Government Complex, it was a natural progression—a chance to apply everything we had learned to reshape the heart of the nation’s public realm.

What is the main vision behind the project, and what does “people-first government” mean in practical design terms on this site?

The main vision is to realign the Government Complex’s physical reality with its fundamental mission: to serve its people. For decades, the campus reflected institutional priorities—order, control, separation. Our vision was to flip that entirely and create a living model of a people-first government.

We prioritised accessibility over authority, transforming car-dominated roads into shaded, walkable promenades. We valued engagement over efficiency, replacing vast, unused plazas with intimate gardens, seating areas, and flexible event lawns. We championed integration over isolation, weaving the complex into the surrounding urban fabric with green connectors and welcoming edges. And we committed to resilience over rigidity, using nature-based solutions to manage climate risks while creating cooler, more comfortable public spaces.

Ultimately, “people-first” here means designing from the human scale upward. It means every design decision answers a simple question: Does this make the citizen feel welcomed, respected, and cared for? The site is no longer just a place of administration; it is a civic place-making.

How did you approach adding 55 acres of hard surface into green social spaces and a central plaza, and how did you decide on what to remove, keep, or add?

Our approach was one of strategic retrofitting rather than a blank-slate redesign. With every square foot as registered state infrastructure, we worked adaptively within the fully built campus. The guiding principle was simple: design for the human experience—for the person on foot. We shifted the core question from “Where do cars go?” to “How do people move, gather, and thrive?”

This led to clear criteria. We removed barriers to seamless movement, prioritizing the elimination of decades of traffic congestion. We kept and repurposed robust existing structures while liberating the ground plane for people. And we added a continuous network of green pathways and vibrant social plazas, weaving nature-based infrastructure with public transit.

Ultimately, we transformed the logic of the complex from separated to integrated, and from obstacle to connection. The result reimagines urban mobility: turning of hardscape into a resilient, people-centric hub for its 40,000 daily users—a new benchmark for how civic space can serve both community and climate.

Can you tell us about the sustainable features of this project, and how did these choices shape the look and feel of the space?

Our sustainable strategy is not just a list of features; it’s the foundational principle that shaped the entire design. We engineered an integrated ecological and social system that fundamentally changed the look and feel of the site.

In essence, we transformed infrastructure into ecology. The most telling examples are how we redefined mobility and repurposed concrete. We rerouted car traffic underground to reclaim the surface for people, creating a network of “Cooling Corridors.” Here, 3,500 new trees and a system of bioswales replaced six lanes of asphalt, lowering local temperatures by 4-6°C and turning sun-scorched roads into shaded, walkable greenways.

This philosophy of transformation extended to every hard surface. A massive 5.5-acre concrete pond became a regenerative “People’s Oasis,” while the rooftop of an 8,000 sqm parking garage was reborn as a vibrant public park—a new green “front door.” We even celebrate functional elements, like turning rainwater pipes into sculptural “gold” features, making the system’s performance visible and beautiful.

Multifunctional Rooftop Utilisation: Repurposing three large parking garage rooftops into a green plaza and health space for all, while increasing green with new design intervention, a solar-powered urban farm that incorporates vertical greenery for food production and rainwater harvesting.

The result is a complete sensory shift: from hot, hard, and car-dominated to cool, soft, and people-centric. The space now feels like a lush, resilient campus where sustainability isn’t hidden—it’s the very experience of comfort, connection, and civic life.

How do you think the new public spaces change the relationship between citizens and their government, and what kinds of activities or behaviours on site matter most to you?

The traditional perception of government is often one of formality, inaccessibility, and emotionlessness. It can feel like an uncommunicative monolith, more focused on its own bureaucrat persona than on the people it serves.

We are working with the site and the habitual pattern of 20 20-year-old governmental campus where the car is king. The goal is to leave behind the old impression of an imposing, unapproachable government. The new space should make it self-evident that the government’s primary role is to serve the people. When the design successfully prioritises human connection and community needs, that message is communicated not through command, but through powerful, mundane experience.

New, thoughtfully designed public spaces at the heart of the government complex can fundamentally flip this script. By prioritising human experience over institutional grandeur, they transform the relationship from one of transaction to one of interaction. The government ceases to be a remote authority and instead becomes the host of a shared, public living room.

What were the biggest challenges of redesigning an existing, formal government complex, whether technical, bureaucratic or climatic, and how did you deal with them?

The greatest challenge was not technical, climatic—those are solvable with expertise and creativity. The true test was navigating the complex bureaucratic environment of a government institution, where overlapping layers of authority and entrenched silos could have easily stalled progress.

Fortunately, we had an exceptional client in Dhanarak Asset Development, led by Dr. Nalikatibhag Sangsnit. Without his visionary leadership and unwavering commitment, our team could not have managed these invisible complexities. He fostered the will to change and created an environment of respect and professional trust.

Over 6.5 years, I learned that the most critical element in transforming a formal government complex is not just design skill—it is building and sustaining that trust. His perseverance, alongside our team’s dedication, allowed us to turn ambition into reality.

What does winning the award for “Landscape Architecture of the Year” mean to you?

For us, it is a profound validation of our team’s commitment to meaningful, regenerative design. But more importantly, for our government client, it is tangible proof that public leadership can—and must—drive ecological and social change. This award underscores that real adaptation happens not just in policy documents, but in the physical reinvention of our shared spaces.

It sends a clear message to governments everywhere: you can lead with action. By reimagining infrastructure as living systems, you directly serve your communities, your workforce, and the climate itself. This project represents a fundamental shift—from top-down planning to co-creating with nature. It demonstrates that a government can be the catalyst, turning vision into a built reality that heals, inspires, and endures.

This isn’t just an award for a project; it’s recognition of a new model for public stewardship.

What advice would you give younger landscape architects who want to influence public policy and urban life through design?

Through collaboration and intergenerational thinking, you are more powerful than you realise. Your most essential tool isn’t just technical skill, but your capacity for care.

I remember walking through imposing government complexes and feeling the architecture’s clear intention: to awe and intimidate. I asked myself, “Why would a governmental design need to make its people feel small?”

As a citizen and landscape architect, I won’t be tasked with tearing those buildings down. Instead, my role is to heal, to soften, and to reconnect. Our mission is to find a way to “communicate” with those who impose power and structures—to wrap them in accessible plazas, connect them with green pathways, and create spaces at their feet that invite people in rather than push them away. Your goal is to introduce a more human-centred, nurturing quality to the civic realm. Never again should a citizen feel small in a place meant to serve them.

Use your designs to foster dignity, belonging, and dialogue. When you succeed, you do more than design a space; you transform the relationship between a citizen and their government and the city. And in that transformation of my care, your care to form a generation, we all benefit.

In this Q&A, we speak with Lotte Scheder-Bieschin, recipient of the Emerging Architect of the Year award at the BLT Built Design Awards, about Unfold Form, a construction system that challenges some of the most taken-for-granted assumptions in contemporary building. Developed within the ETH Zurich Block Research Group, the project rethinks how concrete floors are formed, proposing a lightweight, reusable formwork that replaces material excess with structural intelligence.

Unfold Form draws on principles of curved-crease unfolding and bending-active geometry to transform flat-packed plywood components into a self-supporting, corrugated formwork assembled on site in just 30 minutes. The system enables the construction of vaulted concrete floors that rely on geometry rather than reinforcement, significantly reducing both concrete and steel while producing an expressive architectural result that is inseparable from its structural and fabrication logic. Tested through full-scale demonstrations in Zurich and Cape Town, the project positions research, experimentation, and construction as a continuous design process rather than separate stages.

In the following questions and answers, Lotte Scheder-Bieschin reflects on her path from structural engineering to architectural research, the hands-on development of Unfold Form, and what it means to receive BLT recognition while still actively shaping the project toward real-world application.

Lotte Scheder-Bieschin // Photo: Lotte Scheder-Bieschin, Andrei Jipa

Can you tell us a bit about your background? What first drew you to architectural design?

I have long been fascinated by how complex geometry and simple physical principles can lead to both expressive spatial qualities and structurally efficient solutions. I initially trained as a structural engineer and became increasingly frustrated by the strong separation between disciplines, which often results in fragmented outcomes. This led me to pursue an architectural master’s programme focused on integrative design, combining computational design, digital fabrication, material behaviour, and structural geometry.

I later continued with a PhD under Professor Philippe Block, whose work on reinterpreting historic structural principles strongly shaped my thinking. I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to pursue this research at ETH Zurich, where the academic environment made it possible to develop the work with both intellectual freedom and strong technical support. Through this path, I found a way to pursue my passion for architectural design while connecting it with real-world constraints such as sustainability, fabrication, and construction.

How would you describe your personal design philosophy and how did it influence your approach to Unfold Form?

I believe that architectural expression can emerge naturally from informed structural and fabrication logic, rather than being applied afterwards. Design is most convincing to me when geometry, structure, and fabrication are developed together. Unfold Form reflects this integrative approach and is conceived as a construction system rather than a fixed form.

Another key aspect of my philosophy is accessibility. Instead of relying on highly specialised fabrication technologies, I am interested in systems that are simple, robust, and broadly applicable, without sacrificing performance.

Unfold Form: Curved-crease un-foldable formwork for sustainable vaulted floors. Photo: Lotte Scheder-Bieschin, Andrei Jipa

How did you come up with the vision for Unfold Form? Was there a specific moment, model or problem that made you think “this could really work”?

The underlying motivation of my PhD was the observation that structurally efficient vaulted concrete floors are rarely built today, mainly due to the cost, waste, and complexity of state-of-practice formwork systems. I therefore set out to explore an alternative formwork approach based on simple geometric principles, in particular curved-crease folding.

The decisive moment came through hands-on experimentation with simple paper models. When I reversed the principle from folding to unfolding, I realised that a flat-folded component could unfold into a structurally effective three-dimensional form with strong potential for rapid on-site deployment.

How would you describe Unfold Form to someone with no background in architecture or engineering, and why does this lightweight, reusable formwork for vaulted floors allow for significant reductions in concrete and reinforcement compared to conventional slabs?

Concrete needs a mould to give it shape while it hardens. In most buildings, this mould is flat, resulting in flat slabs that require large amounts of concrete and steel reinforcement. Corrugated vaulted floors, by contrast, use geometry to carry loads more efficiently, mainly through compression, allowing a significant reduction in concrete and eliminating the need for reinforcement. However, formwork for such geometries is far more complex than flat panels and is often produced as one-off, waste-intensive moulds using digital fabrication. This added complexity and waste can limit applicability and undermine the sustainability benefits of vaulted floors.

Unfold Form addresses this challenge by using a lightweight kit of components made from simple plywood plates that unfold on site into a corrugated vaulted formwork. The result is a more sustainable construction system that reduces material use and waste, while also introducing a distinct architectural character expressed through the ribbed vault visible from below.

What happens during the 30 minutes of assembly, from the moment the flat-packed, low-cost elements arrive on site to the moment the formwork is ready for casting, and how does this fast setup make the system adaptable to both high-tech and low-tech construction environments?

The formwork components arrive on site flat-packed, which makes transport and handling efficient. A small team can unfold and connect the elements into a stable frame without heavy machinery or specialised labour. This speed and simplicity significantly reduce on-site effort and coordination, making the assembly process robust and reliable for construction practice.

Equally important is how the components are made. They are fabricated using simple two-dimensional cutting processes and basic assembly tools, rather than advanced multi-axis machines typically used for complex formwork. This makes the system adaptable to both industrialised and resource-constrained construction environments.

Unfold Form: Curved-crease un-foldable formwork for sustainable vaulted floors. Photo: Lotte Scheder-Bieschin, Andrei Jipa

What were the most difficult moments in the development of Unfold Form and how did you navigate them as a student leading a research-driven project?

One of the main challenges was scaling up from small experimental models to architectural-scale prototypes while ensuring structural reliability and repeatability. This required extensive work on computational modelling, structural design, detailing, and fabrication testing, particularly for the curved hinges, which were resolved using textile connections.

A particularly memorable moment came during the large-scale unfolding, when we saw how precisely the formwork geometry developed and verified that it could safely carry our weight. That was a powerful confirmation that the concept was viable.

What, if anything, would you do differently if you could redesign or re-build Unfold Form now, knowing what you know from the Zurich and Cape Town demonstrations?

The demonstrations confirmed the robustness of the core idea, while also revealing opportunities to further simplify connections and logistics. Future development will focus on improving scalability. At the same time, I am keen to explore additional design possibilities, including aggregated vaulted floors, barrel vaults with parallel corrugations, and funnel-shaped columns, which build on the same underlying principles while expanding the architectural and structural range of the system.

How does it feel to receive an “Emerging Architect of the Year” award while still a student, and how does that recognition affect your confidence, your sense of responsibility, or even the pressure you feel about what comes next?

I am very grateful for the recognition. It is especially important to me to share this moment with my team, including Mark Hellrich, and my advisors, Professor Philippe Block and Dr Tom Van Mele, as well as the many other supporters involved.

It is encouraging to see that research-driven, system-oriented design approaches are recognised beyond academia. The award brings motivation and confidence to continue developing Unfold Form, and it also comes with a sense of responsibility to pursue the project further and work towards making a meaningful contribution.

What are your long-term ambitions for Unfold Form and for your own career? Where would you like this system to be used in the future, and what advice would you give to other students who want to tackle big structural and environmental questions through design?

My next goal is to bring Unfold Form into practice through a spin-off: www.unfold-form.com. I am currently exploring the most suitable strategy while continuing to address the technical challenges required for large-scale application. There has already been interest from different regions, and I would love to see the system realised in built projects, particularly in housing, education, and low-carbon construction. More broadly, I hope the system can contribute both sustainable benefits and architectural quality across a wide range of contexts.

For students, my advice is to focus on a clear underlying system, test ideas physically, and persist. Rigorous design can lead to meaningful change.

In this interview, we speak with Lisa Van Staden, winner of the Emerging Interior Designer of the Year award at the BLT Built Design Awards, about Symphony, her proposal for the Museum of South African Languages. Developed at Cape Peninsula University of Technology and set within the Cradle of Humankind, the project examines how language, sound, and cultural identity can be translated into space.

Symphony draws on the logic of sound waves, using a fragmented façade to express rhythm, movement, and diversity. Each vertical element shifts in depth and alignment, responding to light and framing the vast horizon of its setting, where the landscape becomes part of the architectural experience. Inside, these gestures produce changing shadows throughout the day, reinforcing the idea of language as something dynamic rather than fixed.

Material choices play a central role in shaping the project’s atmosphere and performance. Timber and rammed earth echo the colours and textures of the surrounding landscape, supporting comfort, climate response, and a strong sense of place. Rather than treating the museum as a static container, Symphony positions architecture as a medium for communication, encouraging visitors to experience language spatially and reflect on its role in human connection.

Lisa Van Staden

Can you tell us a bit about your background? How did you decide to make a career in design?

I grew up in Cape Town, South Africa, and from a young age, I naturally gravitated toward anything creative. I was always drawing, painting, or paying close attention to beautifully designed spaces and objects. While I did well enough in school subjects like mathematics or economics, I always felt most confident and most myself in design-related work. It was the one area where I excelled without forcing it — it felt intuitive. Over time, I realised that design wasn’t just something I enjoyed; it was something I needed to pursue. Choosing a career in interior architecture became a way to combine creativity, problem-solving, and my love for transforming ideas into physical experiences.

How did your personal background and experiences growing up in South Africa influence your approach to this project?

I wouldn’t say my personal background directly shaped the concept, but growing up in South Africa definitely influenced the scale of my thinking. When I received the brief — a museum of South African languages — I felt inspired to think boldly and creatively. South Africa is incredibly diverse, with 11 official languages, each tied to complex cultural identities. Understanding this diversity made me want to approach the project with depth, respect, and ambition. Rather than designing something ordinary, I wanted to challenge myself to create a concept that celebrates the richness of communication in this country in a meaningful, poetic, and innovative way.

What is the vision behind Symphony and why did you decide to express the idea of South African languages through a building form that behaves like a sound wave?

The vision behind Symphony is rooted in sound — specifically, how sound shapes language. Growing up in South Africa, English has always been my first language, but I’ve always been fascinated by the unique sounds of the other languages spoken around me. The way people move their tongues, shape their mouths, and create specific sounds is something I find so beautiful.

I started thinking about communication itself: how do we understand each other? What is physically happening when we communicate? That line of questioning led me to sound waves. Every word we speak exists as a pattern of sound, and each language has its own rhythm. With so many languages in South Africa, there are countless sound patterns and expressions. I wanted Symphony to capture that idea of movement, diversity, and energy — the physical expression of sound. The building needed to feel alive, as if someone’s voice had been frozen in space.

How did you conceive and develop the fragmented façade so that each section echoes the movement of a sound wave while also catching light differently and framing the almost endless horizon of the Cradle of Humankind?

This was one of the most enjoyable parts of the design process. I didn’t want to base the façade on just any random sound wave — I wanted the form to have meaning. So I recorded myself saying the word “language” on my phone. I then used the waveform from that voice note as the literal foundation for the building’s form. That exact sound wave became the fragmented silhouette of Symphony.

Because the Cradle of Humankind has a flat, almost infinite horizon, the vertical fragments of the façade create a striking contrast against the landscape. The horizon acts as “silence” — the flat line that appears on a sound wave when nothing is being said. As you move toward the building, the fragmented form rises from that silence like a sound coming to life.

On top of that, the reflective pond at the front of the building mirrors the upper half of the façade, creating the illusion of a complete sound wave. As you walk from one side to the other, the building shifts rhythmically, catching light differently and framing the endless horizon between each fragment. This merging of architecture and nature reinforces the idea that sound — and communication — is something that flows, evolves, and exists in constant motion.

Could you explain how your design responds to dynamic environmental or experiential conditions?

In Symphony, the concept of the sound wave is fully embedded in the architecture, not only in elevation but across the entire building form. When viewed in plan, the building mirrors the exact same sound-wave pattern seen on the façade. This is achieved through the strategic placement of walls that shift in and out, creating a rhythmic motion that mimics the movement of sound.

These walls are positioned at varying depths and heights, generating a dynamic interplay of light and shadow as the sun moves throughout the day. Sunlight passes through and around these staggered wall elements, producing a sense of continuous motion — as if sound is physically travelling through the space. This changing light condition animates the interior and enhances the building’s experiential quality, reinforcing the idea that Symphony is a spatial translation of sound itself.

What materials have you selected and why? Are they locally sourced or appropriate to the context?

The materiality of Symphony is intentionally tied to its setting within the Cradle of Humankind, a landscape known for its rich natural textures and earthy tones. Timber and rammed earth were selected because they can be locally sourced with the right research, making them contextually appropriate and environmentally responsible choices.

Rammed earth directly uses the surrounding soil, meaning the landscape itself becomes the building. This allows Symphony to blend naturally with the site while benefiting from rammed earth’s excellent thermal performance. Timber can also be sourced from the region and provides a warm, tactile quality that complements both the architecture and the natural environment. Together, these materials reinforce the connection between the building and its land, grounding Symphony in the cultural and geological identity of the Cradle of Humankind.

How does your building encourage cultural communication or engagement?

Symphony is designed as a physical and conceptual translation of sound — one of the oldest and most universal forms of communication. By shaping the entire building as a sound wave, Symphony becomes a place where visitors can experience communication spatially rather than only verbally. The in-and-out movement of the walls visually expresses the rhythm and pattern of sound, symbolising the connection between people, language, and shared experience.

Its location within the Cradle of Humankind strengthens this intention. As a site deeply rooted in human origins, it becomes the ideal setting for a building that celebrates how people interact, express meaning, and connect across cultures. The interior pathways guide visitors through shifting light and shadow, creating moments of pause, reflection, and engagement — encouraging them to think about the evolution of communication and their relationship with one another. Through form, movement, and environment, Symphony becomes an active reminder that communication is at the core of our shared humanity.

How does your design support user experience, comfort, and well-being?

Symphony supports user comfort and well-being through both spatial and environmental strategies. The rhythmic arrangement of walls filters natural light throughout the day, reducing glare and creating a softly illuminated interior. This promotes visual comfort while reinforcing the building’s concept of movement.

The excavation of the structure into the landscape improves thermal performance, helping maintain stable indoor temperatures and enhancing occupant comfort. The use of natural materials such as timber and rammed earth further contributes to a calming sensory experience — these materials regulate humidity, reduce harsh acoustics, and visually connect users to the surrounding natural environment.

Walkways and openings allow fresh air, framed landscape views, and controlled daylight into the building, supporting mental restoration and emotional well-being. Combined with its cultural concept, these design choices ensure that Symphony is not only visually meaningful but also a comfortable, restorative environment for all users.

How do you feel about winning the BLT Built Design Award?

Winning this award has left me genuinely overwhelmed — in the best way. I constantly remind myself that hard work really does pay off. I don’t carry pride or feel above anyone; I try to stay grounded in humility, always knowing that none of this would have been possible without God’s guidance. As much as we sometimes think we can do everything on our own, I truly believe this recognition is a blessing I could never have achieved without Him.

This prize makes me feel empowered. It makes me feel young, strong and capable — like a thriving female interior designer who is ready to take on the world. It reminds me that there is nothing I cannot accomplish if I commit myself fully. I’m extremely grateful for this recognition, and I’m excited for everything that lies ahead in my interior design career.

How do you see your future as a designer after Symphony, and what advice would you give to other students who want to engage seriously with cultural identity and language in their interior architecture work?

I see myself thriving as a designer who is not afraid to explore new ideas and create work that has never been done before. My goal is to design with intention, originality, and cultural depth — bringing my African roots into every project in a way that feels authentic, contemporary, and meaningful. I want my designs to tell stories: stories of identity, place, communication, and the beauty of being African in a global design world. I believe that the future of my career holds endless opportunities to innovate, to lead, and to show through my work that creativity is limitless when you stay true to who you are.

Receiving this recognition has reminded me that hard work truly pays off. I feel empowered, grateful, and inspired to keep pushing boundaries and trusting my abilities. I see myself becoming a strong, young female interior designer who contributes something fresh to the design industry — someone who is confident in her craft but grounded in humility.

What advice would you give to students?

Always trust the process, even when it feels overwhelming. Stay curious, stay open, and never be afraid to ask questions. Consistency is more important than perfection — small steps every day will get you further than you think. Stay true to your own voice and identity, because your background and your story are what make your work unique. And lastly, remember that passion shows in your designs; when you love what you’re creating, the work naturally becomes stronger.

In this interview, we sit down with Beom Kwan Kim to discuss VINE, the project awarded Construction Product Design of the Year at the BLT Built Design Awards. Developed by the University of Ulsan and Studio Kwan, VINE draws from the quiet intelligence of natural growth, translating the logic of climbing vines into a building envelope that generates energy, responds to climate, and reshapes the relationship between architecture and technology. Through AI-driven design, robotic 3D printing, and curved BIPV modules, the façade becomes more than a surface, operating as a living system tested at full scale in Ulsan. Grounded in research yet proven in practice, VINE points toward a future where architectural expression, fabrication, and environmental performance evolve together.

Beom Kwan Kim // VINE. Photo by yoon_joonhwan.

Can you tell us a bit about your background?

My work has always moved between industrial design and architecture. I don’t see them as separate fields, but as two ways of asking the same question: how do we make things that can exist in the real world—technically, socially, and emotionally?

I began studying industrial design in Ulsan, a city where manufacturing and material culture are part of everyday life. That environment taught me early on that design is not only about form, but about systems—production, technology, and application.

Later, I studied architecture at the Architectural Association (AA) in London. AA expanded my perspective from objects to buildings and urban conditions, and introduced me to experimental design thinking and computational methods. At the same time, it strengthened my interest in fabrication, material logic, and the user experience—sensibilities that came from industrial design.

Afterwards, I worked across the UK and Asia on projects of multiple scales, from product and industrial design to architecture and urban work. Those experiences reinforced my belief that architecture is not simply spatial composition, but an integrated process where materials, technology, environment, and human life converge.

Today, at the University of Ulsan, I continue to teach, research, and practice in parallel. My focus is on computational design, material experimentation, robotic fabrication, and renewable energy systems—especially research that is site-specific, experimentally validated, and scalable, rooted in local environments and regional industrial technologies.

What is the inspiration behind VINE, and what problem were you trying to solve?

VINE began with a simple but fundamental question: What should the role of architects and designers be for the next generation? I wasn’t interested in making something that was only creative or visually pleasing. I wanted to ask what kind of design is actually necessary today, given the relationship between people, cities, and the environment.

Conceptually, VINE is inspired by the way vines grow: starting from the earth, climbing surfaces, and reaching toward light. That natural logic helped me reinterpret the building envelope as something more than a boundary—more like a living, responsive skin of the city.

The practical problem was also clear. Conventional flat BIPV panels often underperform on façades, they limit architectural freedom, and they tend to remain as attached technical devices rather than integrated architectural elements. So we asked:

What if a building envelope could grow like a living organism—respond to the environment—and generate energy by itself?

VINE is our experimental and empirically validated response. It integrates natural growth logic with AI-based design, robotic fabrication, and renewable energy into one architectural system.

How would you explain VINE simply to someone unfamiliar with BIPV or 3D printing?

When people hear “BIPV” or “3D printing,” they often assume it’s complicated—so I begin very simply. VINE is a façade that behaves like a vine reaching for sunlight. The building’s outer skin doesn’t just sit there; it reacts to light.

Most solar panels are flat, and on vertical walls, they struggle to catch sunlight efficiently. VINE replaces that flat logic with many small, curved, multi-angled modules, creating a textured skin. Because each module faces the sun a little differently, the façade captures light more effectively—especially in summer.

And VINE doesn’t stop at generating energy. It is designed as a system that absorbs sunlight, produces electricity, stores it, and reuses it when needed—so the building can operate more like a self-sustaining organism than a passive structure.

The modules are made with large-scale robotic 3D printing, enabling complex curved shapes without moulds and using eco-friendly materials such as biodegradable PETG and recycled plastics. On-site, it works like modular cladding: easy to install, easy to replace, and practical to maintain.

How did you develop the geometry so it can be mounted on real buildings?

Honestly, this was one of the most difficult parts. The project started from an intuitive idea—an organic, non-linear geometry integrated with photovoltaics—but turning that into a buildable system is a different problem entirely.

Form changes directly affect solar performance, structural stability, and constructability, so the geometry could not remain arbitrary. We needed integrated research where geometry, performance, and construction details could be resolved at the same time.

That is why we developed an AI-based design tool that analyses EPW climate data, solar paths, shading conditions, and orientation. Each module is generated and adjusted based on those inputs. In that sense, VINE’s geometry is not simply an aesthetic gesture—it is data-driven and performance-based.

In parallel, we developed a hybrid structural system combining steel and timber, along with standardised connection details. Through repeated prototyping, testing, and validation, the façade evolved into a modular system that remains complex in appearance but feasible in construction.

How did robotic 3D printing enable the curved multi-angle modules?

Large-scale robotic 3D printing was a key technology for VINE. Conventional BIPV production is based on mould-driven flat manufacturing, which fundamentally restricts curved and multi-angled geometries. Robotic fabrication allowed us to move beyond that limitation.

Without moulds, we could fabricate non-linear curved modules with precision. Using a multi-axis robotic arm, we controlled extrusion angles, thickness, and local transparency to guide daylight, reduce self-shading, and maximise solar incidence according to orientation and sun angles.

VINE is not a repetition of identical panels. It is a parametric family of modules—unique in geometry, but unified as one buildable system. In the prototype and demonstration, around 136 modules were installed, each generated through multiple parametric variables..

Material choices were equally important. We used biodegradable PETG and recycled industrial plastics so that sustainability is embedded not only in the idea but in the manufacturing process itself. In that sense, robotic 3D printing became an architectural production strategy integrating geometry, performance, material, and environmental responsibility.

How did sun-path studies guide the design, and how did you achieve such high summer performance?

In VINE, sun-path analysis was not a final check—it was the starting point. We didn’t design a form and then optimise it; we allowed solar behaviour to generate the form.

Using EPW climate data, seasonal sun paths, solar altitude/azimuth, and shading simulations, we informed not only the overall façade direction but also each module’s local angle, curvature, depth, and spacing. That is why every module is differentiated by its position and exposure.

Summer performance was especially important. When the sun is high and intense, flat BIPV systems often suffer from inefficient incidence angles and thermal losses. VINE addresses this with multi-angled curved geometry that receives solar radiation more orthogonally across the day while reducing self-shading.

The differentiated geometry also creates micro-gaps for ventilation and micro-shading, helping dissipate heat and reduce thermal buildup—a major cause of efficiency drop in summer conditions.

In short, sun-path studies did not optimise a fixed design; they generated a responsive, climate-aware energy façade.

VINE. Photo by yoon_joonhwan.

How is VINE made and assembled on site?

VINE was designed as a buildable and maintainable system from the beginning. Fabrication, assembly, and maintenance were not afterthoughts—they were part of the design.

Modules are fabricated off-site using large-scale robotic 3D printing. Each geometry is generated through an AI-based workflow and translated directly into robotic fabrication data. This enables complex forms without moulds, while maintaining precision. Around 136 unique modules were fabricated for the demonstration system, all different in shape but unified by one structural logic.

After printing, modules are combined with standardised photovoltaic components and connection interfaces, pre-assembled into transportable units, and delivered to the site. This prefabrication reduces on-site time and minimises construction errors.

On-site, a hybrid structural frame of steel and timber is installed first. Modules are then mounted using standardised mechanical connections. Because each module is digitally indexed, installation remains systematic even when no two modules are identical.

Maintenance is equally modular: each unit can be detached and replaced independently, and PV components are accessible for inspection and service. VINE is therefore scalable, replaceable, and serviceable—connecting experimental geometry with long-term operation.

What were the main challenges, and how did you resolve them?

The hardest part of VINE was meeting three demands that usually conflict: sculptural freedom, renewable energy performance, and manufacturability. Expressive geometry can reduce efficiency, while performance-driven solutions often become formally restrictive. For this project, choosing one at the expense of the others would have weakened its purpose.

We treated these constraints not as competing priorities but as conditions that must inform each other. That required a long, iterative process: AI-based solar simulations, parametric adjustments, structural analysis, and physical prototyping—repeated many times.

Collaboration with engineers was essential. A buildable system needs more than algorithms; it requires structural logic and realistic construction strategies. Through that collaboration, we developed a hybrid structural system and standardised details that preserved complexity while remaining feasible.

Finally, validation mattered. VINE needed to work in real conditions, not only in simulations. The Ulsan demonstration at HD Hyundai Construction Equipment became the turning point—allowing us to verify energy output, structural stability, and economic viability at once. That real-world proof shifted VINE from an experimental idea to a credible architectural energy system.

How do you feel about receiving the “Construction Product Design of the Year”?

Receiving “Construction Product Design of the Year” is an honour, but more importantly, it feels like recognition of an approach rather than a single object. VINE started as a question: can a building envelope become an active system—responsive to climate, generating energy, contributing to its surroundings—rather than a passive surface?

Being recognised in a construction product category is significant because it suggests that research-driven and experimental ideas can transition into buildable, scalable systems. What makes the award especially meaningful is that it acknowledges not only formal innovation, but also performance, manufacturability, and real-world feasibility.

VINE was developed through extensive prototyping, AI-driven simulations, robotic fabrication, and on-site demonstration in Ulsan. The fact that its energy output, structural stability, and economic potential were validated gives this recognition real weight.

Personally, it also resonates with my background across industrial design and architecture. It reassures me that working across disciplines can produce new possibilities for future building systems.

How will VINE influence your future work, and what advice would you give young designers?

I don’t see VINE as a conclusion. I see it as a point along a longer process. The project reaffirmed my belief that architecture today must be developed as integrated systems—where performance, technology, material, and environmental responsibility are designed together, rather than treated separately.

I’m also not sure I’m in a position to give advice. I still feel that I am learning, questioning, and searching in much the same way as many younger designers. What I can share is an experience: that ideas only become real when they are tested under real conditions.

The demonstration project in Ulsan was a turning point for me. Building the system, measuring its performance, and validating it on site shifted the work from speculation to evidence. Going forward, I hope to continue developing projects that combine computational design, material experimentation, robotic fabrication, and renewable energy systems—always grounded in implementation and verification.

Through the process of submitting this work to competitions and external reviews, I also realised how important it is to test ideas beyond one’s own discipline, context, or environment. Having work evaluated from different perspectives—technical, cultural, and geographic—often reveals questions and insights that are not visible from within a single field. For me, this kind of external validation has become an essential part of design research.

If there is one thing I would like to share, it is this: you don’t need to start with definitive answers. What matters is having questions that feel necessary, and staying with them long enough to test them thoroughly. I hope these explorations become collective—shared with architects, designers, and researchers across different fields and countries—because that is where the future of architecture and design truly begins.

Finally, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the BLT Awards jury and organising committee for recognising this work and for providing such a meaningful platform for dialogue. This opportunity to share the ideas behind VINE through the award and this interview is deeply appreciated.

Widely acclaimed and recognised as one of India’s most iconic architecture and design practices, Sanjay Puri Architects has long occupied a distinct position within the global architectural landscape. Led by Sanjay Puri, the Mumbai-based studio is celebrated for a body of work that is both instantly recognisable and rigorously contextual, defined by expressive contemporary forms shaped by climate, culture, and a deep understanding of place. Across typologies and scales, the practice has consistently challenged conventional boundaries, producing architecture and interiors that are as experiential as they are precise.

With more than 250 awards to date, including international recognitions from the World Architecture Festival, LEAF Awards, ArchDaily, Architizer, and WA Community, the firm’s influence extends far beyond India. Sanjay Puri Architects is repeatedly cited among the world’s leading design studios, earning a reputation for work that balances sculptural ambition with technical clarity and human-centred thinking. Each project, whether architectural or interior in scope, reflects a careful orchestration of movement, light, and material, resulting in spaces that engage the senses while remaining grounded in their context.

This philosophy is powerfully embodied in the Aatma Manthan Museum, recipient of the BLT Built Design Awards – Interior Design of the Year. Located beneath the monumental Statue of Belief in Nathdwara, Rajasthan, the project presented an extraordinary challenge: to create a meaningful interior experience within a complex, irregular structure at the base of a 369-foot-high statue. Rather than approaching the museum as a conventional container for artefacts, Sanjay Puri reimagined it as a spatial meditation, a sequence of immersive environments designed to guide visitors inward.

In this interview, Sanjay Puri reflects on how his early, hands-on training shaped his design instincts, how mythology and philosophy informed the museum’s conceptual framework, and how architecture can move beyond representation to become an emotional and psychological journey.

AATMA MANTHAN MUSEUM. Photo: VINAY PANJWANI // Sanjay Puri

Can you tell us a little about your background? How did your experience shape the way you approached designing this project?

I started working with an architectural firm at the age of 18, prior to joining architectural school for a formal education.

I had completed multiple sets of working drawings and details, site visits to interior and architecture projects, and meetings with clients before joining an architectural school.

This practical knowledge allowed me a very comprehensive understanding of materials & processes. There are multiple interior sites where sketches have been made directly on site, with lines, angles or curvatures marked directly and then executed as opposed to drawing everything in an office.

This was the attribute that helped create this free-flowing fluid space for the Aatma Manthan Museum. While the basic planning was done in the office with multiple sketches, the execution on site was overseen and modified to achieve the derived fluidity.

What were your first thoughts when you were invited to create a museum dedicated to “aatma manthan” under a 369-feet statue, and what brief did you give yourself before you began sketching?

The very first thoughts were to create a museum with various aspects of Lord Shiva. We researched his story, the numerous names he was known by and thought of creating different spaces to depict different aspects based on history.

Based upon mythology, Lord Shiva attained spiritual divinity after a long period of meditation. Upon learning this aspect, we decided to create a series of experiential spaces that are meditative or contemplative in nature, instead of a museum with artefacts and writing.

The essence of his spirituality came from the soul (aatma), mind (mana), and body (tann) being one, holistically.

It is this aspect that became the key value to be experienced by the design.

How did you translate the triad of soul (aatma), mind (mana) and body (tann) into the design? What kind of journey did you want visitors to experience as they move through the museum?

Our intention was to move beyond a traditional artefact-based museum and instead create a meditative spatial journey inspired by Lord Shiva. As we studied his mythology, we were drawn to the idea of spiritual oneness achieved through deep meditation, where soul (aatma), mind (mana) and body (tann) exist in harmony.

This triad became the core design principle. Each zone of the museum evokes one aspect — from sensory awareness to introspection — ultimately guiding visitors toward a unified, contemplative experience. The museum is designed as an inner journey, mirroring Shiva’s path to spiritual alignment.

How did you tackle the irregular floor plan and manage to create a clear sequential flow of spaces, rather than a museum that feels fragmented?

We looked at the irregular shape as a challenge & made multiple configurations to fragment the overall volume into different spaces with different experiences. Lord Shiva has 108 names. A number totalling 9 is very auspicious in Hinduism.

Our final plan created 18 rooms of varying sizes based upon the column grid & available space.

These spaces are entered sequentially by orchestrating the circulation path through carefully placed openings.

What guided your decision to work with a neutral palette throughout, and how did colour, light and material help you support the audio-visual and immersive installations?

We needed the space to be neutral throughout to enhance the impact of the sound and light in the immersive spaces.

The neutral grey was chosen with specific controlled lighting to calm the mind immediately upon entering the lobby.

The sound, along with colour and light, is themed in each room. The first room only has the elements of fire, water & earth. One room has the universe depicted. The sounds are meditative as well as informative, based on the rooms.

What were the most challenging design or coordination moments in this project, whether technical, conceptual or client-related, and how did they change the project along the way?

The most challenging aspect was aligning everyone involved toward a non-traditional museum experience. Instead of narrating the history or mythology of Lord Shiva, we proposed a sequence of immersive, meditative spaces that reflect how Shiva himself attained spiritual transcendence. Convincing stakeholders to move away from conventional displays and embrace a purely experiential, contemplative approach required extensive discussions, but ultimately strengthened the project’s clarity and purpose.

How do you imagine a visitor moving through the museum for the first time? What emotional or mental transformation would you hope they feel between entering and leaving?

We imagined visitors moving slowly through each space, letting the space guide them into a quieter, more reflective state. The intention was for them to experience the gradual calm that meditation brings — not just while inside the museum, but even after they leave.

The client has shared that many visitors naturally respond this way, describing how the spaces ease their senses and leave them feeling noticeably calmer.

AATMA MANTHAN MUSEUM. Photo: VINAY PANJWANI

How do you feel about receiving this award for “Interior Design of the Year”? What does it mean for you personally?

It is an honour to receive the Interior Design of the Year award from BLT — not just for us as architects, but for the clients and every consultant, contractor and craftsperson who contributed to the project.

Personally, it means even more. This design was simple yet radical in how the initial brief was re-interpreted and transformed. Knowing that the space positively impacts hundreds of visitors every day already makes the project deeply fulfilling. Receiving such a significant award for it adds a profound sense of satisfaction and meaning.

What, if anything, would you refine if you could revisit the Aatma Manthan Museum today?

We would not want to change anything yet since it is being positively experienced by numerous people daily.

What advice would you give to younger designers who want to engage with spiritual or introspective themes without slipping into cliché or empty symbolism?

There is a real need for spaces that genuinely calm the senses. My advice is to focus on creating environments that naturally encourage meditation, reflection and quiet — rather than relying on symbols or decorative references.

If the space itself feels peaceful and helps people slow down, it will convey spirituality in a sincere and meaningful way.

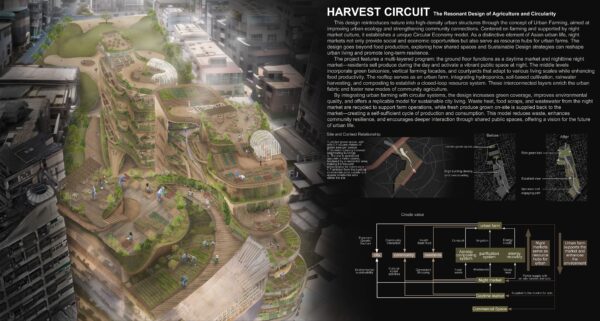

At first glance, Harvest Circuit feels like an ambitious urban farming concept. Look closer, and it reveals itself as a full-blown system where food, people, waste, energy, and shared space are all part of the same daily rhythm. The project, created by Ho Sin Chang from Chung Yuan Christian University in Taiwan, earned her the title of Emerging Landscape Architect of the Year at the BLT Built Design Awards for good reason.

Instead of treating sustainability as an add-on, Harvest Circuit builds a circular economy directly into a dense urban structure. A market on the ground floor shifts from daytime produce sales to a night market after dark. Above it, shared courtyards and vertical farms become part of everyday life. On the roof, hydroponics, rainwater harvesting, and composting quietly run the system in the background. Market waste feeds the farm, the farm feeds the market, and the building functions as one continuous loop.

What makes the project especially compelling is how naturally it connects infrastructure with community, as growing food, sharing tools, composting, cooking, and trading all happen within the same architectural framework. It is a project that doesn’t just talk about sustainability but designs it into daily habits. We spoke with Ho Sin Chang about how Harvest Circuit came to life, the challenges of designing a closed-loop system as a student, and what this recognition means as she steps into her career.

Ho Sin Chang on Building a City That Feeds Itself

Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you first became interested in landscape architecture and topics like urban farming and circular systems?

As an architecture student from Taiwan, I’ve always been intrigued by how spatial design can shape social relationships and ecological systems. My interest in landscape architecture grew from exploring how cities can be reimagined as productive and sustainable environments. Urban farming and circular systems, in particular, captivated me because they address urban issues holistically by combining food production, resource reuse, and community building.

What is the vision behind Harvest Circuit, and how did the project first come to you as an idea or problem you wanted to solve?

Harvest Circuit began with a question: how can we reintegrate nature into high-density cities in a way that goes beyond green decoration? I wanted to address the fragmentation between food systems, public life, and resource waste in cities. The vision was to create a hybrid infrastructure that not only produces food but also fosters circularity and social interaction—reshaping how urban spaces function at multiple levels.

How does Harvest Circuit practically integrate urban farming into a dense urban structure to improve ecology and strengthen community ties, and what kinds of interactions between residents and the farms do you imagine day to day?

The design incorporates urban farming across different vertical layers, from balconies and façades to rooftops, ensuring it’s embedded in everyday routines. Residents grow their own produce, exchange food, compost together, and use shared farming tools. These interactions promote ecological awareness and create stronger neighbourhood bonds through a sense of shared purpose.

How does the night market culture support the project, and in what ways can it help generate a circular economy through shared spaces, shared resources and more sustainable habits?

Night markets, a vibrant part of Asian urban life, are reimagined here as engines of circularity. Food scraps and waste heat from vendors are recycled into compost and energy for farming. In return, the urban farm supplies fresh produce back to the market. The market space also serves as a social and economic hub, encouraging sustainable habits through informal education and shared resource use.

How did you organise the layout, from the daytime/night market on the ground floor to the vertical farms and courtyards in the middle and the rooftop farm above, and how do these different levels work together to make the project function as a single system?

The layout is organised as a vertical loop. The ground floor hosts daytime produce sales and transforms into a night market. The middle floors contain shared kitchens, vertical green walls, and adaptive living units. The rooftop integrates hydroponics and rainwater harvesting. Each level is linked by physical connections and resource flows, making the whole building operate as a unified circular system.

How do the rooftop hydroponics, rainwater harvesting, composting and waste recycling actually work together to form a closed-loop system, and what kind of impact do you hope this has on waste reduction, greenery and urban resilience?

The rooftop system captures rainwater for irrigation and collects organic waste for composting. Hydroponics is powered by recycled heat from the market. These systems reduce dependency on external inputs and lower waste output, while increasing urban greenery and food security. The goal is to enhance urban resilience through decentralised, adaptive infrastructure.

What were the main challenges you faced while developing Harvest Circuit, whether technical, spatial or conceptual, and how did you resolve them as a student designer?

One major challenge was balancing complexity and clarity—creating a multi-layered system without overwhelming the spatial logic. As a student, I relied on iterative modelling and feedback from mentors to refine each layer’s function. Integrating the social, ecological, and technical systems harmoniously required continuous testing and simplification.

How do you feel about receiving the “Emerging Landscape Architect of the Year” award for this project, and what does this recognition mean to you at this stage in your career?

It’s truly an honour. This recognition affirms that student projects can have a real impact when they respond to urgent urban issues with innovation and empathy. It gives me the confidence to keep pursuing interdisciplinary design strategies and fuels my ambition to work on future-focused, socially responsible projects.

What, if anything, would you change or add to Harvest Circuit if you had the chance to develop it further now, whether in terms of program, technology or community involvement?

I’d focus more on participatory design—working directly with local vendors and residents to co-create the spaces and systems. Technologically, I’d like to integrate smart sensors to monitor water, energy, and waste flows in real time, which could help refine the circular processes further.

How do you see your future as a designer after this project, and what advice would you give to other design students?

This project reinforced my belief that designers can be systems thinkers and agents of change. In the future, I want to keep working at the intersection of architecture, ecology, and social systems. My advice to fellow students: don’t be afraid to tackle complex problems—embrace experimentation and stay curious.

The BLT Built Design Awards announce the opening of submissions for the 2026 edition, inviting architects, interior designers, landscape architects, construction innovators, and emerging talents to present their most accomplished and thoughtful work. As one of the world’s most internationally recognised programs dedicated to the built environment, the BLT Built Design Awards celebrate projects that demonstrate design excellence, technical mastery, cultural relevance, and a meaningful contribution to shaping our cities, spaces, and communities.

The launch follows the unforgettable 2025 and 2024 Winners’ Celebration in Basel, Switzerland, where the global design community gathered to honour outstanding work from more than 60 countries. The evening made clear how deeply the Awards resonate across continents, bringing together established firms, independent creators, academics, developers and young designers who share the same dedication to responsible and intelligent design.

Reflecting on the success of the past season, co-founder Astrid Hébert shared: “The ceremony in Switzerland felt incredibly special. Seeing renowned practices and first-time student winners stand proudly on the same stage was truly moving. The BLT Built Design Awards have become a place where diverse perspectives meet: designers from different cultures, climates, and disciplines all presenting work rooted in meaning and purpose. With the 2026 edition now open, we’re excited to welcome another year of ideas and projects that enrich the global conversation about the built environment.“

Submissions to the BLT Built Design Awards 2026 will be reviewed by an extensive panel of respected professionals whose expertise spans architecture, interior design, landscape architecture, construction, academia and industry innovation. The current jury includes Samantha Lassoudry, Founder and Chief Designer at Lassoudry Architects; Christian Brendelberger of Dietziker Partner Baumanagement AG; Anastasia Ignatova, Urban Planning and Design Expert; Andreas Rupf, Head of ETH RAUM and Founder of SPEKTRUM GmbH; Muhammad Habsah of U+A, part of the 10N Collective; Mona Vijaykumar, Associate Urban Designer at Perkins&Will; Cas Esbach, Founder of KANS and Professor at SCAD; Tran Ngoc Danh, Vice President of the Vietnam Design Association (VDAS) and Founder of VMARK Vietnam Design Award; Christina Chen-Chiao Kuo, Founder and Creative Director of Kuuo Living Limited; Omar Zhan, Co-founder and COO of Surfaice and the “Construction Voices” AI digest; Amir Idiatulin, Founder and CEO of IND; Zhou Yi, Chief Designer at Dayi Design; and Rudi Stouffs, Dean’s Chair Associate Professor and Assistant Dean (Research) at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore.

They are joined by Osaru Alile of CC Interiors Studio; Pal Pang, Chief Creative Officer at Another Design International; Juliet Kavishe, Executive Board Member of the Pan Afrikan Design Institute; Sandra Baggerman of Trahan Architects; Des Laubscher, Co-Founder and CEO of the Greenside Design Center, College of Design and Hannah Churchill, Founder and Design Director at hcreates interior design, and more big names in the industry. Together, they ensure a rigorous, insightful and globally informed evaluation process.

The program’s scope is reflected in its previous winners. In recent editions, Zaha Hadid Architects were honoured for the King Abdullah Financial District Metro Station in Riyadh; Sanjay Puri Architects received recognition for the Aatma Manthan Museum in Rajasthan; LANDPROCESS, led by Kotchakorn Voraakhom, transformed the Thailand Government Complex into a regenerative landscape; VINE, created by the University of Ulsan and Studio Kwan, introduced a new photovoltaic façade system; and emerging designers such as Lotte Scheder-Bieschin of ETH Zurich and Lisa Van Staden presented forward-thinking work that captivated both jurors and the global audience.

Winners of the BLT Built Design Awards receive significant international exposure. Their work is featured on the official BLT website, published in the annual BLT Awards Book of Design, shared across global press and partner networks, and celebrated at the next awards ceremony. This gathering continues to grow in scale, prestige and visibility. For many firms and emerging designers, the Awards have become a platform that elevates their work, expands their audience and opens new professional pathways.

With submissions now open, entrants are encouraged to take advantage of the 10% Early Bird discount available until March 31st, 2026. The BLT Built Design Awards 2026 welcome completed projects, conceptual work, prototypes and student submissions from every region of the world. Whether exploring new construction methods, redefining interior experience, shaping public landscapes or presenting thoughtful architectural strategies, the Awards seek projects that demonstrate clarity, intention and a meaningful contribution to the built environment.

Submissions for the BLT Built Design Awards 2026 are now open at bltawards.com.

A record-setting ceremony that brought together world-renowned studios, award-winning architects and a new generation of emerging designers for a night dedicated to creativity, collaboration and the future of design inside one of Basel’s most iconic cultural spaces.

On Friday, November 21st, 2025, Basel became the centre of the international design community as the BLT Built Design Awards and the SIT Furniture Design Award came together for their largest celebration to date. Two hundred guests from more than thirty countries, from China, Japan, Thailand, South Korea and Vietnam to the United States, Canada, Costa Rica, Argentina, South Africa and New Zealand, gathered inside the spectacular Elisabethenkirche, the 19th-century neo-Gothic landmark now transformed into one of Switzerland’s most striking contemporary cultural venues.

The decision to host the ceremony in the Elisabethenkirche underscored the awards’ shared values, honouring innovation, craftsmanship and adaptive reuse design at a moment when architecture and furniture design continue to respond creatively to the challenges of the built environment.

The evening brought together the winners of the 2024 and 2025 BLT Built Design Awards and the SIT Furniture Design Award, presenting both trophies and certificates on stage, accompanied by a seated gala dinner. Designers, architects, product innovators, academics, students, media partners and jury members connected throughout the evening, turning the neo-Gothic space into a lively international meeting point.